Recently, South Africa’s Minister of Home Affairs Aaron Motsoaledi lost a court fight that, in all honesty, nobody could have expected him to win. Likewise, he probably thought he’d end up losing it. Both ethical and practical considerations led to his dismissal. He can’t revoke the benefit that the South African government gave to Zimbabwean refugees over 15 years ago because of this.

Zimbabweans seeking refuge from the economic and political unrest in their home country were allowed to enter South Africa in April 2009. The law explicitly granted them this authority. The Zimbabwe Dispensation Project was the initial effort to establish a system to provide short-term housing for refugees from Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe Exemption Permission replaced the former Zimbabwe Special Permission in 2017. For the duration of their visas, Zimbabweans who arrived during the crisis of 2008–2009 were given full freedom of movement but were denied citizenship for themselves and their children.

The Department of Home Affairs has decided to withdraw the special dispensation in 2021, following a grace period that will extend until the end of 2022 and allow Zimbabweans to regularise their situations. Based on their qualifications and employment opportunities, some of the individuals were to be awarded residency and work visas, while the remaining individuals were to be sent back to Zimbabwe. About 178,000 persons could have their ZE residency status changed as a result of the verdict. Zimbabwean law stipulated that children born in South Africa were entitled to and expected to acquire Zimbabwean citizenship, but were prohibited from doing so.

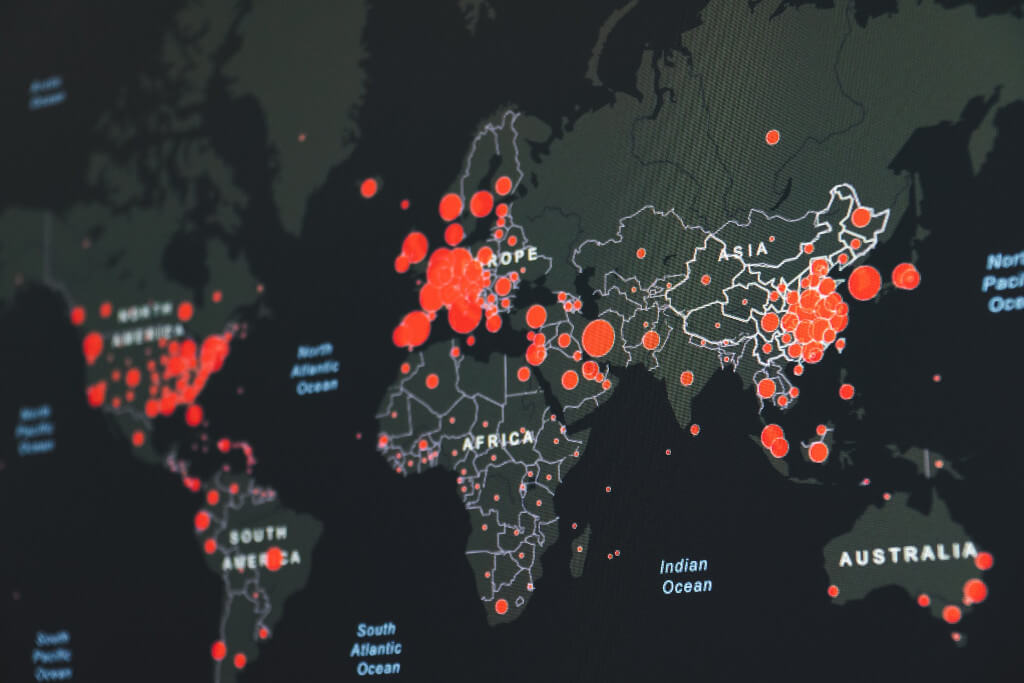

In comparison to the 3.96 million immigrants in South Africa (as reported by StatsSA), the 178,000 constitute a negligible fraction of the population. The vast majority of registered Zimbabweans have college degrees and work experience. For the past 15 years, most of them have thrived in the South African economy. Why can’t the status of law-abiding Zimbabweans already living under the permission be made official?

Many more undocumented migrants in other parts of Africa and the world have been granted legal status. Refugees from Mozambique who had fled to South Africa were granted regular status once the country’s civil conflict ended. However, the Minister of Home Affairs was unable to follow this course of action because of South Africa’s anti-immigrant mentality. Therefore, he decided against participating in a legal process in which he would almost certainly lose.

I’ve been reading up on African migration policy, particularly the 2018 approval of a protocol for the free movement of individuals by the African Union. According to my findings, this has the potential to facilitate both economic expansion and the integration of markets.

South Africa looks to have a fluid policy towards immigration. In 2017, cabinet members unanimously approved a white paper outlining proposed reforms to the country’s immigration system. There has been no movement on policy documents and legislative reforms concerning labour migration that were issued over a year and a half ago. It has been a while since the promised new immigration white paper was made public. Some of the suggestions, including a points system to replace the vital skills list, could streamline migration policies. The suggested quota system in the draught bill was just one example of an alternative that would have only served to further complicate matters.

Should the system be changed before the 2024 general election? Most likely not at all. This is the most pressing problem that needs fixing. The administration is cautious about moving on immigration policy because of the ensuing polarisation. Our study aims to demonstrate how South Africa could learn from the successful migration policy reforms implemented in other nations, both in and outside of Africa.

Prejudice Against Foreign-born Individuals

Politicians are notorious for their hostile rhetoric towards immigration and those who make a living off of it, but ideas that are both feasible and on the table are often masked as something else and occasionally even passed. The corporate labour permit is just one example; another is the growth in the number of African nations whose citizens do not need a visa to visit South Africa. The process of hiring skilled foreign workers is being simplified. Reforms will be enacted under the guise of anti-immigrant sentiment.

This is hardly a South African phenomenon. For the fiscal year ending in December 2022, “long-term immigration” to the United Kingdom hit 1.2 million, an increase of 221,000 from the previous year. It comes as the government of that country is promising to deport illegal immigrants to Rwanda and counting on “stopping the boats” to win over the public.

Georgia Meloni, the newly elected prime minister of Italy in part due to her anti-immigrant beliefs, has taken a similar tack by allocating work licences for 425,000 non-EU migrants to enter the nation until 2025. This will go on till Meloni leaves office. Liberal Democrat Laura Boldrini has said that the high quotas show a hint of submission.

A migration textbook advises readers to “not equate political rhetoric with policy practice” while considering migration policies. It’s not surprising that many countries’ immigration regulations appear vague or difficult to understand. In the current climate, it seems hard to reform migration policy.

However, Africa’s ability to economically integrate is crucial to the continent’s ongoing economic success. Most countries are quite small, economically speaking, therefore free movement of people across borders is essential for effective integration.

Other African governments, especially those of more prosperous countries, have not been as reticent as South Africa’s to alter migration limits. East Africans and West Africans (members of ECOWAS) have advanced further economically than their southern and northern African counterparts. African nations have much to gain from studying the practises of other African nations and regions, not simply those of the European Union and South American countries.

The Migration Governance Reform in Africa (MIGRA) initiative is led and managed by the New South Institute. Both the idea behind the MIGRA project and its basic structure are covered in our most recent working paper.

The Southern African Development Community (SADC), the East African Community (EAC), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), and the African Union are all being studied for their migration policies and practices. We think African countries and regions can learn as much from each other as they can from people all around the world. Over the next year or two, papers will be published on each of these eight cases as they are finalised. In addition, we will be creating novel forms of media in which to engage in two-way communication with the public and policymakers.

Our prior work provides instructive examples of novel reform ideas from all around Africa. East and West African countries have a wide range of options for accommodating migrants who cross borders for a variety of reasons and at different times. Even in southern Africa, progress is conceivable, as evidenced by a recent deal between Namibia and Botswana allowing inhabitants of both nations to cross their common border using merely identity cards. South Africa and Kenya’s new visa-free travel agreement is just the latest example of how visa-free travel is spreading throughout the continent. There are many other instances like this to think about.

Both the cautious optimism for recent achievements in migration governance across the African continent and the widespread unhappiness and uncertainty regarding migration policy served as inspiration for our endeavour. It’s feasible that this will help improve practice and maybe even political discourse to some extent. The South African government will likely offer amnesty to Zimbabwean exemption permit holders and their children, as it did to 220,000 Mozambican refugees in December 1996.